If you like this guitar lesson, be sure to check out Larry Carlton’s interactive guitar courses 335 Blues and 335 Improv.

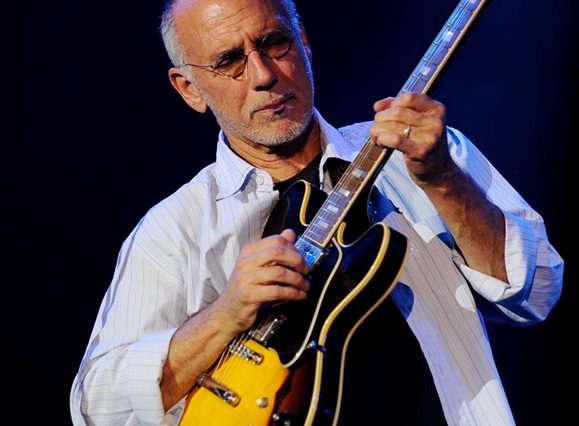

Before Larry Carlton, session guitarists were a highly skilled, but anonymous subset of the 6-string community. A few studio cats—such as Howard Roberts and Tommy Tedesco—had developed name recognition through solo albums and GP columns, but it was Larry Carlton who first brought star power to the gig.

In the ’70s and early ’80s, Carlton’s sweet, singing tone and soaring lines inspired a generation of pickers to attend music school so they, too, could play rock and blues with a jazzbo’s finesse. Arguably, Carlton’s licks did more than any enrollment drive to entice guitarists to attend Musician’s Institute and Berklee College of Music.

Armed with his trademark sunburst Gibson ES-335 and a Sho-Bud volume pedal, Larry Carlton played on more than 3,000 sessions for artists as diverse as Michael Jackson, John Lennon, and Dolly Parton. Carlton’s phrases on Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark, Steely Dan’s Royal Scam, Donald Fagen’s The Nightfly, and the theme for Hill Street Blues epitomize the golden age of studio guitar.

Unlike scale-oriented guitarists, Larry Carlton typically builds his distinctive solos around wide interval jumps. In a May ’79 Guitar Player cover story, he touched on his “chord-over-chord” approach to soloing.

Now, more than three decades later, we take you deep inside his intriguing technique. Read on for the full guitar lesson including audio, tab, charts, and more…

Guitar Lesson

Part 1: http://truefire.com/audio-guitar-lessons/money-notes-1.mp3

Part 2: http://truefire.com/audio-guitar-lessons/money-notes-2.mp3

Click here to download the power tab for this guitar lesson.

Eureka!

“I started playing when I was six,” recalls Carlton. “Country music was popular in the late ’50s in Southern California, so on Saturday night I’d see Jimmy Bryant, Joe Maphis, and Larry Collins performing on TV. In fact, when I was nine or ten, I went to Bakersfield to play with Buck Owens on his television show. But before long, I got into jazz. I started teaching myself more ‘adult’ chords by studying records by Barney Kessel, Joe Pass, Wes Montgomery, and Johnny Smith. One day, I was walking to junior high school—no guitar—thinking about a chord I’d learned, G13b9. As I was visualizing it on the fretboard, it hit me: This is an E triad on top of a G chord.

“Here’s G13b9 [plays Ex. 1a]. You can see an E triad on the top three strings, and the G7 chord on strings six, four, and three. Really, it’s a mix of two sounds—G7 and E. Because it’s voiced on the lower strings, the G7 is the foundation, while E contains the colorful extensions.”

To fully grasp the concept, strum the two voicings in Ex. 1b—a G7 (G, F, B, D or root, b7, 3, 5,), and a second-inversion E triad (B, E, G#). Now compare these voicings sonically and visually to the previous G13b9 grip. Do you see how it contains three notes from G7, as well as the E triad?

“For me,” continues Carlton, “this was a huge breakthrough. I intuitively understood that to improvise over G13b9, I could weave an E arpeggio into a G7 arpeggio [plays Ex. 1c]. I began to explore this idea by playing licks that merged these two arpeggios. This technique gave me possibilities that didn’t feel or sound like I was running a scale—pretty exciting stuff for a 14-year-old. To get used to the stretches, try practicing figures like this [plays Ex. 2a]. To hear how these arpeggios work against the harmony, have someone play a G13b9. Or, if you’re practicing by yourself, include a G13b9 within the line, like this [plays Ex. 2b]. Part of the challenge is knowing how long to linger on the upper triad. That depends on the context—the tempo, the musicians, the audience—and there’s no set formula. Sometimes all you need is a hint of the upper triad, like this [plays Ex. 2c].”

Diminished Discoveries

As the teenage Carlton explored his chord-over-chord discovery, he began to see a larger pattern. “Soon I realized that that E triad was part of a G diminished scale,” he details, “which is built from alternating half- and whole-steps. Jazz players use this scale to solo over altered dominant chords, such as the G13b9 we’ve been playing.”

Ex. 3a contains a one-octave G diminished scale. To find the E triad lurking within it, think of Ab enharmonically, and you’ll see G#, B, and E, a first-inversion E triad.

“Once I made the connection to this G diminished scale,” he elaborates, “I saw that it contained other triads, as well. In fact, you can play a major triad off of each tone in a Gdim7 chord [plays Ex. 3b]. This gives you a total of four triads: G, Bb, Db, and E [plays Ex. 3c]. In the end, it all adds up to a diminished scale, but my brain and eyeballs see it as a series of related triads.

“Back in the ’70s, people said I didn’t play linear solos, and that’s because I wasn’t thinking about scales. Where someone else might play a diminished pattern like this over G13b9 [plays Ex. 4], I’d try to work through these triads [plays Examples 5a and 5b]. It’s a simple concept, and I wind up playing a lot of the same notes as those who favor scales, but my lines sound different because they’re based on wider intervals. Don’t get me wrong—you can get nice lines from a diminished scale. For example, this sounds cool against a G7#9 [plays Ex. 6a]. Yet compare it to this triad-based phrase [plays Ex. 6b], which takes some unexpected twists and turns. I’m constantly working on this diminished stuff, because there’s a lot of music in it. John Coltrane—the way he eats up a raised 9 chord? I want to know how to do that.”

Major Realizations

“Because I didn’t know any better,” says Carlton, “I looked for other ways to use this chord-over-chord theory. Soon I started hearing other chords than G13b9 as a combination of triads. For instance, Cmaj7 suggested a G triad sitting on top of a C chord [plays Ex. 7a]. Eventually, I found that you could locate that second triad by simply alternating major and minor thirds from the root of any major chord.”

Ex. 7b illustrates the process. Starting from a C root, we stack major and minor thirds to create a pair of triads: C and G. “Working off that upper triad—in this case, G—gives you a fresh sound,” Carlton reveals. “You can play a G lick, like this [plays Ex. 8a], or move through a G arpeggio [plays Ex. 8b]. Either way, you’re playing from the 5.”

To appreciate Carlton’s overlaid colors, it’s crucial that you hear them in the proper setting. Without the Cmaj7 ringing in the background, these figures sound like the kind of nice, normal G phrases that decorate country and pop songs. But played against Cmaj7, the licks acquire a restless energy.

“It’s funny how that works,” says Carlton. “Context is everything. Of course, you can use this technique in any key. Like over a Gmaj7, I’ll play a D triad.” Play the two chords in Ex. 9a, and then scrutinize Ex. 9b to see how the alternating major and minor thirds create a D triad as an extension of the G triad.

“Instead of arpeggiating a D triad, I might drop a D major pentatonic line over the Gmaj7,” states Carlton, playing Examples 10a and 10b, which you can also view as B minor pentatonic moves. “By themselves, these could be Allman Brothers licks, but they sound jazzy when you slide them against a Gmaj7. The beauty of this approach is that you get new sounds from familiar fingerings.”

Minor Details

You can use the chord-over-chord concept to solo over minor harmony, as well. Against a backdrop of Am7, for instance, try arpeggiating an Em triad. After listening to Ex. 11a’s Am7 and Em, look at Ex. 11b and notice how the order of the alternating thirds is reversed: This time, we’re climbing a minor third/major third ladder. Though the intervals have flipped flopped, we’re still playing off the 5.

“You can get bluesy with the chord-over-chord technique,” says Carlton, playing Ex. 12a. “Instead of picking a standard A minor pentatonic line, try this Em-over-Am approach. Or play an E minor pentatonic line against Am7 [plays Ex. 12b]. Again, it’s a matter of drawing new sounds from old friends.”

Larry Carlton’s Coda

“My chord-over-chord theory won’t explain everything,” says Carlton, “but I’ve found it’s a quick way to get to the ‘money notes’ when diving into a solo. People often ask me, ‘How do I learn to hit the right notes when I solo?’ My advice is simple: Learn harmony. Once you know what notes go into a particular chord, you can base your lines around them, and you won’t get lost. The key to playing great melodies lies in understanding chords. Like everyone else, that’s something I’m still learning.”

If you like this guitar lesson, be sure to check out Larry Carlton’s interactive guitar courses 335 Blues and 335 Improv.